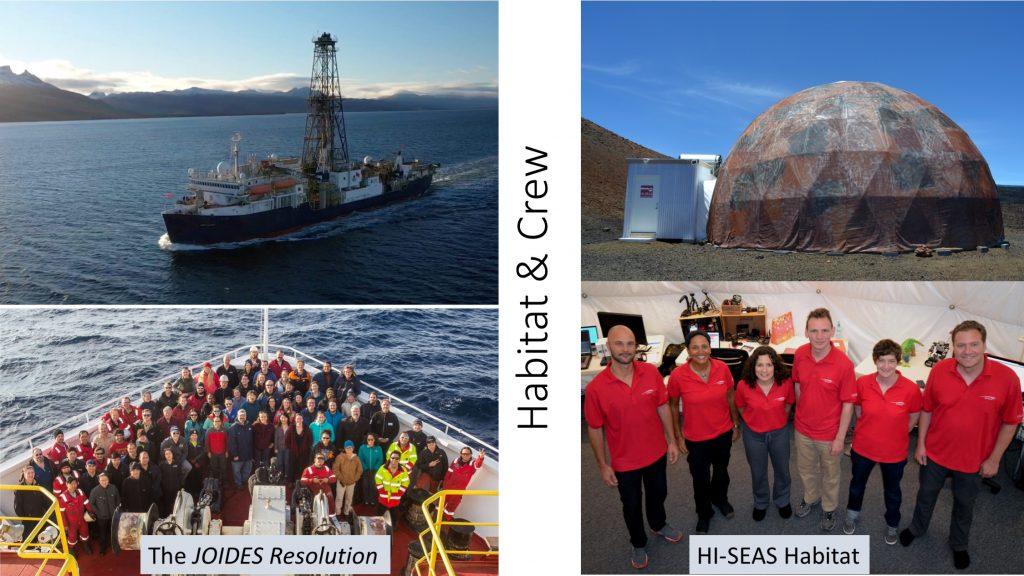

When I say I am an analog astronaut, the first response I get is, “What’s that?”. An analog astronaut is a person who participates in human spaceflight training and/or simulations while on Earth. For me, that means living in Moon and Mars simulations for various lengths of time. I lived in the Mars Desert Research Station, located in Utah, for 2-weeks and in the LunAres habitat, in Poland, for 2-weeks. But the analog simulation that is most similar to this JOIDES Resolution expedition is my 4-month NASA funded Hawai’i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) Mars mission. Space agencies like NASA are very interested in how to successfully send humans to the Moon, Mars, and beyond for long durations. How do you select a crew that can get along for multiple years in a small space, in a hostile environment, and not want to kill each other? There are multiple examples of people already successfully doing this on Earth. Antarctic field stations, submarines, and research vessels like the JOIDES Resolution can work as analogs for space exploration.

The location of an analog mission depends a lot on the specific factors being studied. If you want to simulate a Mars-like environment then you look for remote, cold, volcanic terrains on Earth. OK, Hawaii isn’t known for being cold, but the HI-SEAS habitat sits at 8,200 feet on the slope of Mona Loa making the habitat not exactly beach-front temperatures. A lot of analogs focus on psychological factors like crew cohesion and, in this case, subjects might never even go outside. So the habitat for this type of analog could be in a metropolitan city. For example, the NASA HERA analog simulation is located at Johnson Space Center.

When I learned that I was going to be on the JR for 2-month traveling to a very remote location of the Southern Ocean, I immediately thought of it as an analog mission. The question mark (?) on the map is Point Nemo. The oceanic pole of inaccessibility. It is the furthest point in the ocean from land. When you are at Point Nemo, astronauts flying overhead on the International Space Station are closer to you than any humans on land. We cruised very close to Point Nemo while on our expedition.

Both the JR and HI-SEAS habitat are space-limited. The HI-SEAS habitat is just 36 feet (11 meters) in diameter and a usable floor space of ~1200 square feet. The JR is 470 feet long and 70 feet wide. A lot of the JR’s space is taken up by fuel, drilling equipment, and supplies. The HI-SEAS habitat was designed for a crew of 6 and I was part of the first crew to ever live in it. What I loved about the HI-SEAS crew was how diverse and international it was and that we were 50% men and women. To be selected as HI-SEAS crew member you needed to meet the minimum qualification for applying to the NASA Astronaut program.

I found the JR to be even more international and diverse. We had 123 crew member sailing on Expedition 383 and that included the scientist, technicians, staff, and Siem crew. We had individuals from 20 different countries. The youngest person was 24 and the oldest was hard to determine but one person has been sailing on the JR for over 30 years. What I really liked was that almost 50% of the scientist were women and there was a good mix between early-career scientist and veteran scientist.

Diversity in space exploration has been shown to be an asset. Analog simulations are helping to lead the way when it comes to increasing diversity and access to human spaceflight research. There are analog popping up all over the world and, as commercial spaceflight expands, the need for well-qualified, space-ready individuals is increasing.

Personal space is something most people value and that can be hard to find in an analog simulation. Luckily, in the HI-SEAS habitat we got our own room with real door. That is a rare luxury in many simulations. The HI-SEAS habitat also had two bathrooms but only one shower. We were limited to showering for 2-minutes twice a week because monitoring resources and conservation is extremely important when it comes to space exploration.

On the JR, almost everyone on board shares a cabin with another person and sleeps on metal bunk beds. Because I arrived days before my roommate, I got to choose which bunk was mine. I chose the bottom – less distance to fall when in rough seas! We worked 12-hour shifts every day on the JR and you are on opposite shift from your bunkmate. I worked the midnight-to-noon shift and my roommate worked noon-to-midnight shift. The general rule is that when you leave your cabin to go on shift you bring everything you need because you don’t return to your cabin until your shift is over. This enables you to have private space for at least 12 hours per day – with 6-8 of those hours being sleep. We shared a bathroom with our neighbors next door and had fantastically hot water for showers – and no time limit.

Mealtime is one of the biggest daily community-building activities you can have in analog. The HI-SEAS mission was specifically funded by NASA to investigate food strategies for long-duration missions. We spent 2-days eating similarly to how astronauts on the ISS currently eat, pre-prepared meals that require little preparation, and 2-days creatively cooking using freeze-dried meats and vegetables along with other shelf-stable ingredients. The crew was responsible for preparing all the meals and we alternated our cooking style every two days for the entire 4-month mission. We also ate our meals together at designated times and had to clean up after ourselves.

We don’t cook any of our meals on the JOIDES Resolution. There is a hired cooking staff that prepares 4 scheduled meals every six hours (5-7 am – 11-1pm – 5-7pm –11-1am). In addition to the scheduled meals, we had snack breaks with cookies, desserts, cheese, etc. in between the meals (3-3:30am – 9-9:30am – 3-3:00pm – 9-9:30pm). There is no shortage of food when sailing on the JR. After eating or snacking, the dishes are also taken care of so that everyone can get back to work.

Regardless if you are living in a Mars habitat or a floating spaceship – food is a universal necessity and enables groups of diverse people to come together and bond. Where you sit, who you sit next too, and how long you linger are all part of the crew cohesion processes. During the HI-SEAS mission, we basically sat in the same exact seats from the beginning to the end. This could be because of the small number of participants or it may symbolize a need to establish consistency. During my JR time at sea, it was interesting to watch how people tended to either sit at the same table or mix it up. There was far more mixing and I believe that helped us to create some cohesion in such a large group of people.

When it comes down to it, it’s all about the science. The reason why analog astronauts live in Moon and Mars simulations is so that they can help advance human spaceflight research. The HI-SEAS Mars simulation had two co-principle investigators who had a grant from NASA but we also had a number of research projects outside of NASA, from various universities along with our own individual research projects. The co-principle investigators do not participate in any of the research or live in the analog. When I applied for the HI-SEAS program I specifically applied to be the science communication outreach officer. My job was to take this new Mars analog site and share all the cool research occurring with the rest of the world. I was a regular member of the crew and participated in all crew activities and research and it was our job to be the research subjects.

The JOIDES Resolution expedition 383 has two co-chief scientists on board who worked with the other scientists to make sure the cores are collected and analyzed as much as possible while onboard. I enjoyed working with the co-chiefs and scientists but my position on the JR is separate from that of the scientists because I am not collecting samples or doing any of the scientific research. I was more like an embedded reporter trying to capture the scientific story unfolding around me instead of a research subject being studied.

Communication is extremely important in an analog or expedition. For both the Mars simulation and JR expedition we had daily meetings to keep on top of all the research and activities happening each day. During the HI-SEAS mission we had a crew commander who was responsible for guiding us through the 4-month mission. On the JR, we had the co-chief scientists, the staff scientist, the operations supervisor, and captain who all worked together to keep us moving forward. One of the things I really liked about the JR is that there were digital monitors located throughout the ship that updated you on the agenda, location, and even current weather. Something unique to analog missions is that you usually have a mission control group that helps trouble shoot issues and monitors your overall progress.

Crew autonomy is a big issue when working in isolated environments for long durations. You have to be able to make important decision because communication with mission control can be delayed due to the distance between Mars and Earth or you are so isolated that access to help isn’t easy. Having some form of command structure enables decisions to be made quick but in both HI-SEAS and on the JR, the commander and co-chief scientists often asked for input from key crew members before making a decision. One unique thing about the JR, that we didn’t have in HI-SEAS, was a full-time medical doctor in case anyone got hurt.

Day-to-day life in the Mars simulation and on the JR were extremely similar. We had set hours we dedicate toward the science and we also had free time where we could unwind and connect with our crew-mates. Working out was an important part of analog life. In the HI-SEAS hab we had a treadmill, exercise bike, and exercise DVD’s and often worked out as a crew. On the JR we had an entire gym – although I don’t recommend running on the treadmill while on a moving boat. Playing games, listening to music, and watching movies were also a common theme.

One of the biggest difference between the Mars simulation and the expedition at sea was what it’s like to go outside. Whenever we left the HI-SEAS habitat we had to be in a spacesuit. That meant for 4-months we never felt the wind against our face. If you had to scratch your nose while in a space suit, you are out of luck. On the other hand, we got to traverse some amazing Mars-like volcanic terrain, crawl into lava tubes, and spend hour exploring the surroundings around the habitat. The inherit danger from going outside the habitat came from trying to navigate unbeaten paths of sharp rocks in a bulky space suit. But, I loved going outside in the Mars simulation.

On the JR, you can only go outside so far before you hit a railing. I was initially terrified about the idea of falling overboard in water so cold that it’s a death sentence. At one point were so far from land that the closest humans to us were when the astronauts on the International Space Station passed overhead. If you got injured, the hospital was 5-days away and that’s why there’s a doctor on board. This JR truly represented the analog of a space ship traveling across a hostile environment. Instead of the void of space separating an astronaut from instant death beyond the ship walls, we had the endless, merciless, freezing cold ocean as our death trap – and the boundary was clear, don’t fall overboard!

Getting together to celebrate birthdays, milestones like the halfway mark, or nights of entertainment occurred in both the HI-SEAS Analog and on the JR. It was fun to see everyone come together and build community and it is always one of my favorite things about analog astronaut living.

One of the big research areas in human space flight is how to overcome some of the psychological hurdles associated with long periods away from family and friends. I saw many parallels between living as an analog astronaut in HI-SEAS and life at sea on the JR. In the HI-SEAS habitat we had a robotic pet study and on the JR we had a pet wall. Some people also had stuffed animals. Having windows to look outside was important and, on the JR, we could easily walk outside anytime we wanted – unfortunately, it was really cold!

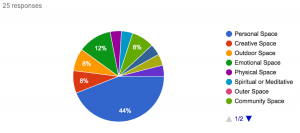

One area of study I have been focusing on is the need for space. Not outer space. I’m talking about the kind of space that feeds a person soul and is a key component to staying sane. I asked 25 people from the JR which type of space, in general, is the most important to them and gave them a variety of choices.

- Personal Space

- Creative Space

- Outdoor Space

- Emotional Space

- Physical Space

- Spiritual or Meditative

- Outer Space

- Community Space

- Quite Space

- Productive/Work Space

- Digital/Virtual Space

- Public Space

- Inner Space

- Other:

Most people chose personal space as the most important, including myself. I’m an introvert by nature and I need personal space to get recharged after a long day of interacting with others. Luckily, the JR had lots of places for me to step away and get my needed personal time. Thinking about types of space that people need to stay mentally healthy isn’t always taken into consideration when designed a habitat, starship, or research vessel but I think more attention needs to be paid to this area if we are going to have successful Moon and Mars colonies.

Something that I am passionate about is looking up at the night sky and, because of the remoteness of analogs, there’s usually good dark skies. I had a contract to shoot for Discover Magazine while in the HI-SEAS habitat and one of my goals was to get good images of the habitat and night sky. So, I spent a lot of nights outside, in a space suit, trying to get the perfect shot.

I was super excited to be heading out to sea on the JR in the southern hemisphere because you can’t really get darker than that. What I didn’t anticipate was the number of cloudy days we’d encounter. But we still managed to see Crux (Southern Cross), the Magellanic Clouds, and even upside-down version of Scorpius and Orion.

My job on both the HI-SEAS mission and JR was to do science communication and education outreach. Both environments offered fun, new challenges for me to overcome. Since the HI-SEAS mission was funded by NASA to investigate food strategies for long duration spaceflight, I decided to run a cooking contest where people from around the world submitted recipes using our “space” pantry of shelf stable ingredients. Then, while in the Mars simulation, I ran a YouTube cooking show called Meals for Mars. It was a lot of fun cooking with a different crew member every week and preparing all the recipes people had submitted. This project led to my Eat Like a Martian TEDx and Meals for Mars cookbook.

While on the JR, I was tasked with doing live broadcasts, something I’d never done before, and I was able to help the expedition scientist connect with people all over the world. A typical session included an introduction to our current location and expedition goals, followed by a tour of the laboratories by tracing the core path as it comes on board. Scientists were stationed at each laboratory to give an overview of the science being conducted and to answer questions. We finished each tour with a 10-15-minute question and answer session. During expedition 383 we completed 23 broadcasts and connected with 10 different countries including 5 different states in the United States. We also worked with the National Science Foundation to hold a Facebook Live event that reached over 2,700 views. I also completed a total of 35 Career Spotlight blogs that highlighted the careers of the expedition crew members and I added at least one post every day to the JOIDES Resolution Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram social media accounts. This resulted in an increase of 89 new Instagram followers, 173 new Twitter followers, and 415 new Facebook page likes over the 2-month expedition. That is a total increase of 677 newly engaged individuals.

But the most fun I had on the JR was shooting 360 images and videos that will be used to create an interactive virtual tour of the JR. I hope to have a link to it by the beginning of August!

Overall, I was surprised by just how similar my two experiences were and can see why these types of extreme scientific expeditions can be used as analogs for human space flight research. I will say that one of the coolest parts about being an analog astronaut in a Mars simulation or at sea is that you get awesome patches to go along with all the amazing memories. I am very thankful for the experiences I have had, the friends I have made, and the science communication education outreach I have done.

Here is my summary video from my JOIDES Resolution expedition. I used the 1-Second Everyday app to compile a 3-second a day snapshot of expedition 383.

Here is my HI-SEAS education outreach video I created to encourage kids to engage in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) activities.